Honoring Jack Ames

March 9, 1941-January 3, 2023

Jack Alfred Ames graduated from Great Falls High School in Montana in 1959, attended American River Junior College, then earned a B.S. in Life Sciences at Sacramento State College in 1967.

During high school and college, he spent summers working as a fisherman and fish buyer’s assistant in Ketchikan and Point Baker, Alaska, and during college, also worked part-time as a veterinary assistant, a truck loader (loading 5-gallon water bottles), a termite damage repairman, and as a Student Research Assistant for a plankton ID and enumeration project at Sac State. In July 1967, Jack took a full-time job as a Junior Aquatic Biologist for the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) on a tuna research project; he was promoted to an Assistant Marine Biologist on the same project after a short time. He probably didn’t know it at the time, but that was the start of an incredible 5-decade career as a public servant at CDFG.

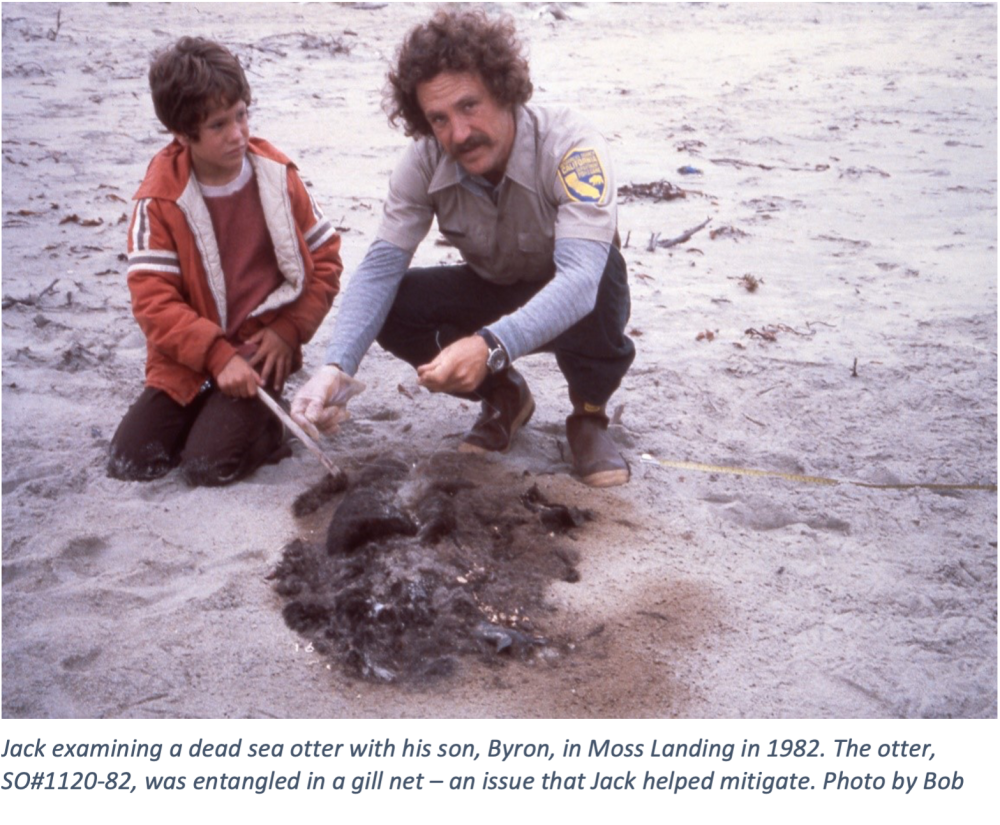

Jack worked as a CDFG fisheries biologist for 5 years, monitoring the albacore tuna fishery and assessing sportfish populations. In July 1972, he transferred from Long Beach to Monterey to join the Marine Region’s (MR) Sea Otter Project. During his early years as a sea otter biologist, he assisted with and led several projects including the design and construction of equipment for several methods of sea otter capture, collection and necropsy of stranded sea otters, and sea otter population monitoring. From the early 80s to the early 90s, in addition to strandings and mortality studies, Jack led or participated in studies designed to understand the effect of various kinds of fishing gear on sea otter mortality, studies to compare the accuracy of various sea otter survey methodology, and studies to refine the capture, transport, and holding of sea otters. He also deployed to Alaska to assist with the recovery and rehabilitation of sea otters during the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill (EVOS) response.

In 1991 Jack was recruited as one of the first employees in CDFG’s newly established Office of Spill Prevention and Response (OSPR). At OSPR, Jack continued to work with his MR colleagues on sea otter research and monitoring and was the go-to expert on sea otters for OSPR. With his extensive knowledge of sea otter biology and his experience at EVOS, Jack started ordering equipment and supplies to make California better prepared for a spill involving sea otters. He also served as the wildlife rehab coordinator prior to the formation of the Oiled Wildlife Care Network. In 1997, OSPR’s Marine Wildlife Veterinary Care and Research Center, a facility designed to wash and rehabilitate oiled sea otters, opened in Santa Cruz. That year the sea otter program was transferred from MR to OSPR, and Jack transferred to the MWVCRC. He continued to lead sea otter stranding response and mortality investigations, spearheaded several studies to improve preparedness for response to oil spills affecting sea otters, and responded to numerous oil spills, rescuing countless oiled animals, until his retirement in 2011.

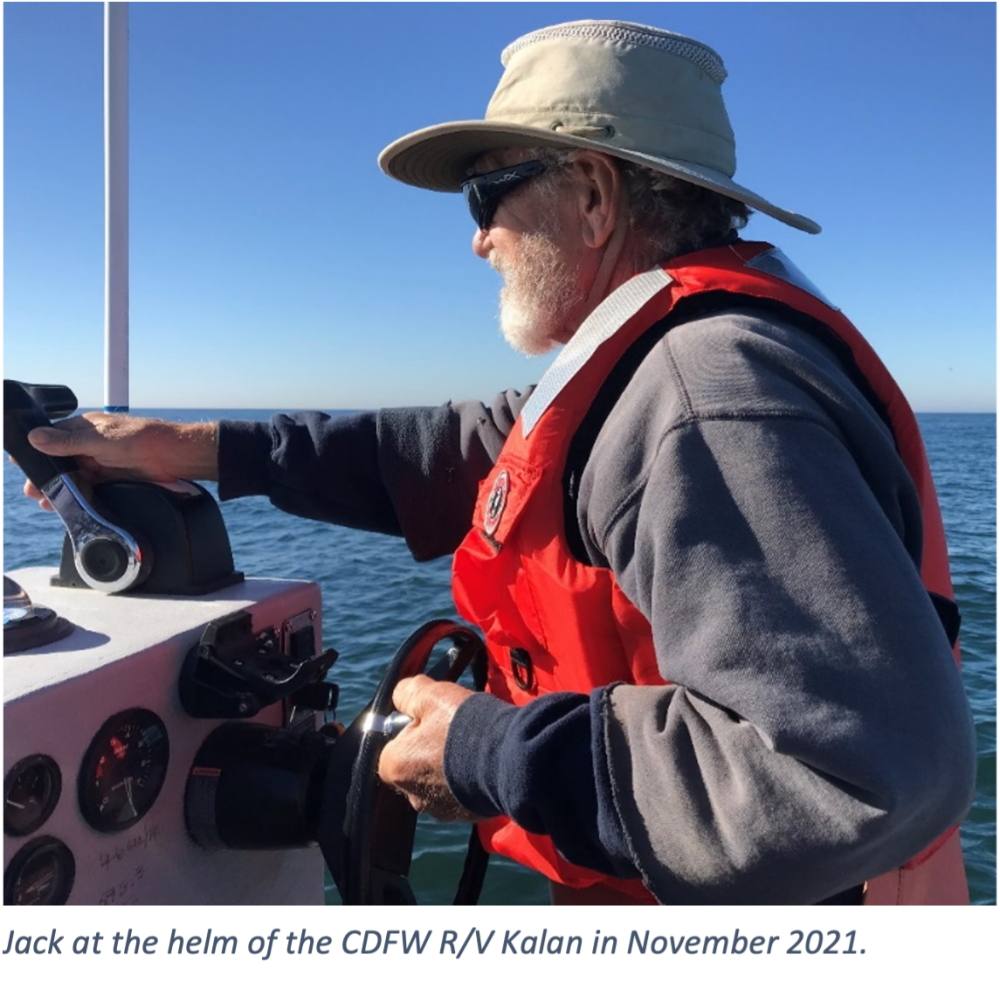

OSPR, and Jack transferred to the MWVCRC. He continued to lead sea otter stranding response and mortality investigations, spearheaded several studies to improve preparedness for response to oil spills affecting sea otters, and responded to numerous oil spills, rescuing countless oiled animals, until his retirement in 2011. Even after 44 years of full-time work for the Department, Jack immediately signed on as a Retired Annuitant and continued to help with sea otter captures, necropsies, population monitoring, oil spill responses, and various other projects on a regular basis through October 2022.

In addition to his core job duties, Jack also assisted with other projects whenever colleagues needed a boat driver or strong field assistant, and he trained and mentored countless students and young scientists. Jack led or co-authored dozens of scientific journal articles and technical reports during his career and logged >2,000 dives as part of the CDFG dive program from 1968 through 2010; the longest active CDFG diving career on record. In 1997 he helped develop BeachCOMBERS, a beached marine vertebrate survey program, and conducted monthly surveys from the program’s inception through 2022. He also initiated and maintained decades-long partnerships with colleagues at agencies, universities, and organizations like the US Fish and Wildlife Service, US Geological Survey, the Monterey Bay Aquarium, The Marine Mammal Center, UC Santa Cruz, Moss Landing Marine Labs, and UC Davis; partnerships that took him to Oregon, Washington, and Alaska for collaborative studies, and many of which still continue today.

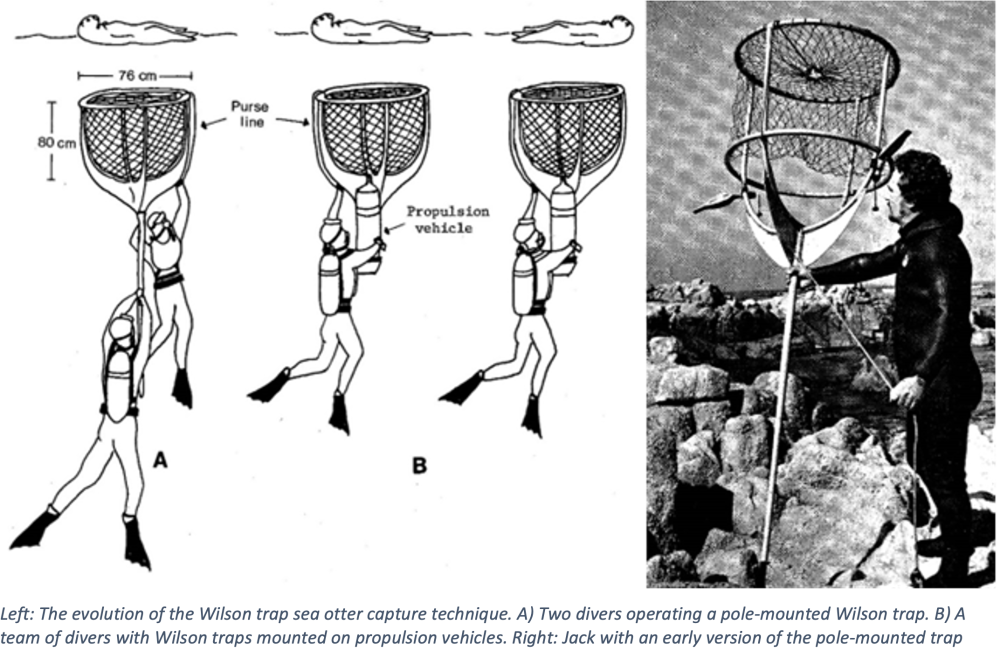

While much of Jack’s work has been widely recognized within the sea otter research and oil spill response communities and beyond, some of his contributions are under-recognized or have only been appreciated by a small subset of colleagues. For example, the Wilson Trap, named after CDFG biologist Ken Wilson, is a piece of equipment now known by all sea otter scientists as the go-to, safe way to capture wild sea otters. Along with Ken and Paul Wild, Jack was heavily involved in the development of the trap and the evolution of the associated capture technique. This work was highlighted in a 1973 episode of Wild Kingdom that featured Jack, and he continued to improve the trap and capture method with colleagues in the following decades.

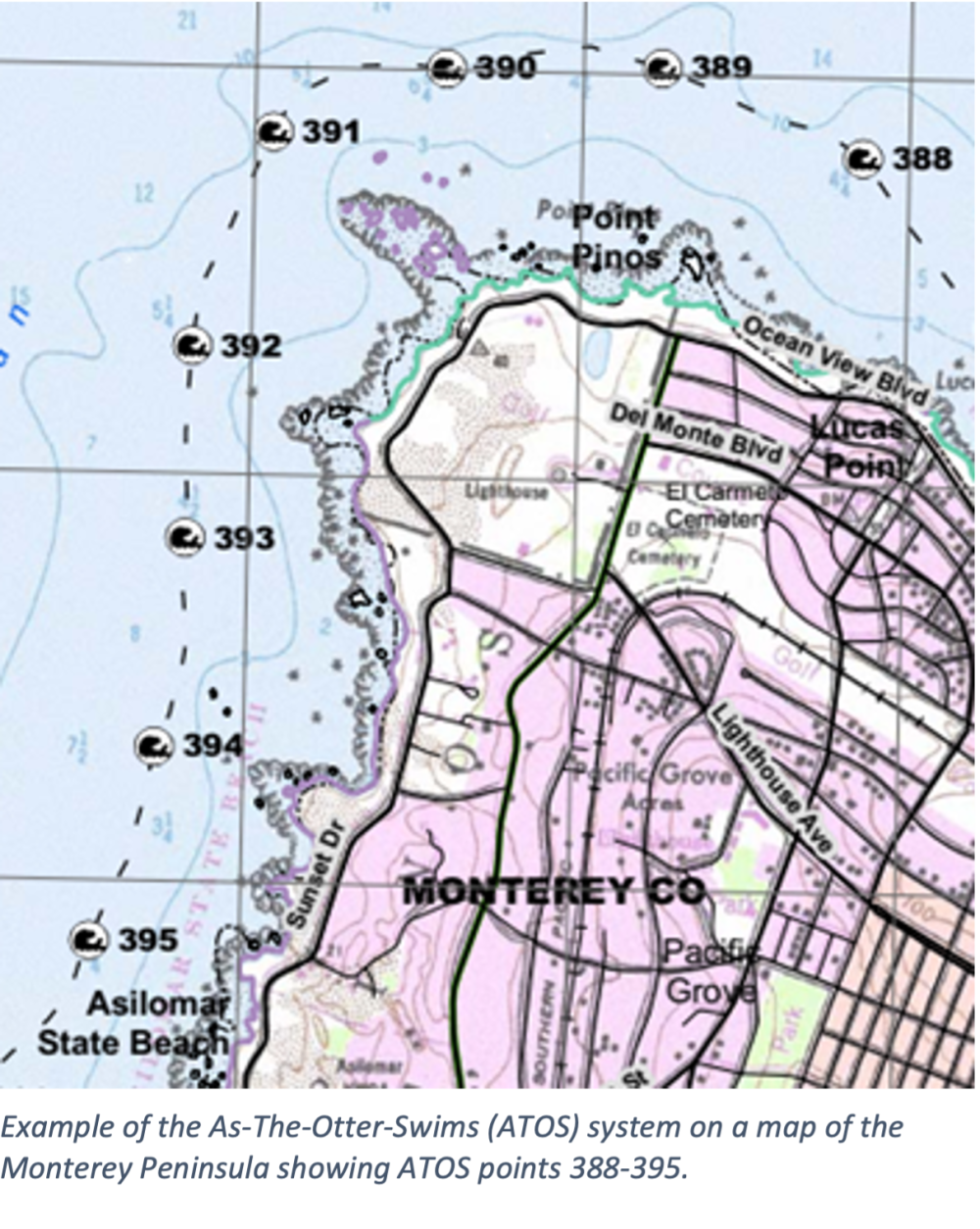

Jack also was instrumental in developing and implementing a unique geographic reference system to record locations and document movements of tagged sea otters along the coastline before the advent of GPS. The As-The-Otter-Swims (ATOS) system started as a set of paper maps with ATOS numbers assigned every 0.5 km along the coast. Soon, this system was adapted to record locations of stranded sea otters and every stranded otter was assigned the ATOS number closest to the stranding location. This system allowed users to easily and quickly calculate distances between animals, summarize location data, and monitor geographical stranding and disease outbreak patterns. Although GPS coordinates are now recorded as well, the ATOS system is still employed and has been used to analyze geographic stranding and tagged otter movement data for numerous studies and has been used in spatial statistics for epidemiological studies of sea otter health risks and the identification of specific environmental risk factors, such as land-sea pathogen transfer.

Additionally, Jack played a pivotal role in distinguishing shark bite wounds from boat propeller wounds on stranded sea otters. He made careful observations about shark bite wound patterns and characteristics, then developed the first criteria for differentiating the wound types. His work led to the re-evaluation and correction of many cases that had originally been mis-characterized as propeller strikes.

Finally, Jack’s work has directly benefitted the conservation of sea otters in California. He was involved in identifying incidental drownings of sea otters in gill and trammel nets as a significant source of mortality, which influenced gillnet restrictions in State waters. He also conducted experimental research on sea otter entrapment in finfish traps that led to the requirement of a rigid 5-inch ring on the fyke openings of the traps to exclude sea otters from entering.

Jack was an incredible field biologist and an old-school naturalist who made observations, asked questions, and made innumerable contributions to the advancement of sea otter research and conservation. However, a successful, influential career is not what defined Jack. What made him extraordinary was his character. He was extremely humble about his accomplishments and accolades, and was also kind, caring, funny, generous, and compassionate. Despite growing up in a time and place where overt racism was the norm, Jack rejected that paradigm and embraced anti-racism. He also was a champion of gender equity before it was a mainstream topic, advocating for and supporting female colleagues in a field that was, until recently, almost exclusively male.

What’s also remarkable about Jack was his community of friends, many of whom started as co-workers and colleagues. The number of his friendships, and the depth of connection, he maintained for decades is inspiring; he was a best friend to many, and a sincere mentor to those who came after him. But perhaps his most endearing quality was his hugs, and boy was Jack a hugger! A hug from Jack was always sure to brighten your day and lift your spirits. In fact, those who knew him could probably use a Jack hug right now.

He loved his family, friends, and animals of all species, and spent his free time hiking, camping, backpacking, and horsepacking in Baja California, Big Sur, and the Sierras. He spent countless hours working on his house and property, helping neighbors and friends, and taking care of the family pets, which through the years included cats, dogs, goats, horses, guinea pigs, and an alpaca, to name a few. Jack was adored by all who were fortunate enough to call him a friend. He will be terribly missed, but fond memories will keep us smiling, as will keeping in touch with those he loved the most: his wife, Bonnie, his children Byron, Terra, and Ruby, and his large community of friends. Tributes, stories, photos, and other remembrances of Jack can be shared here.